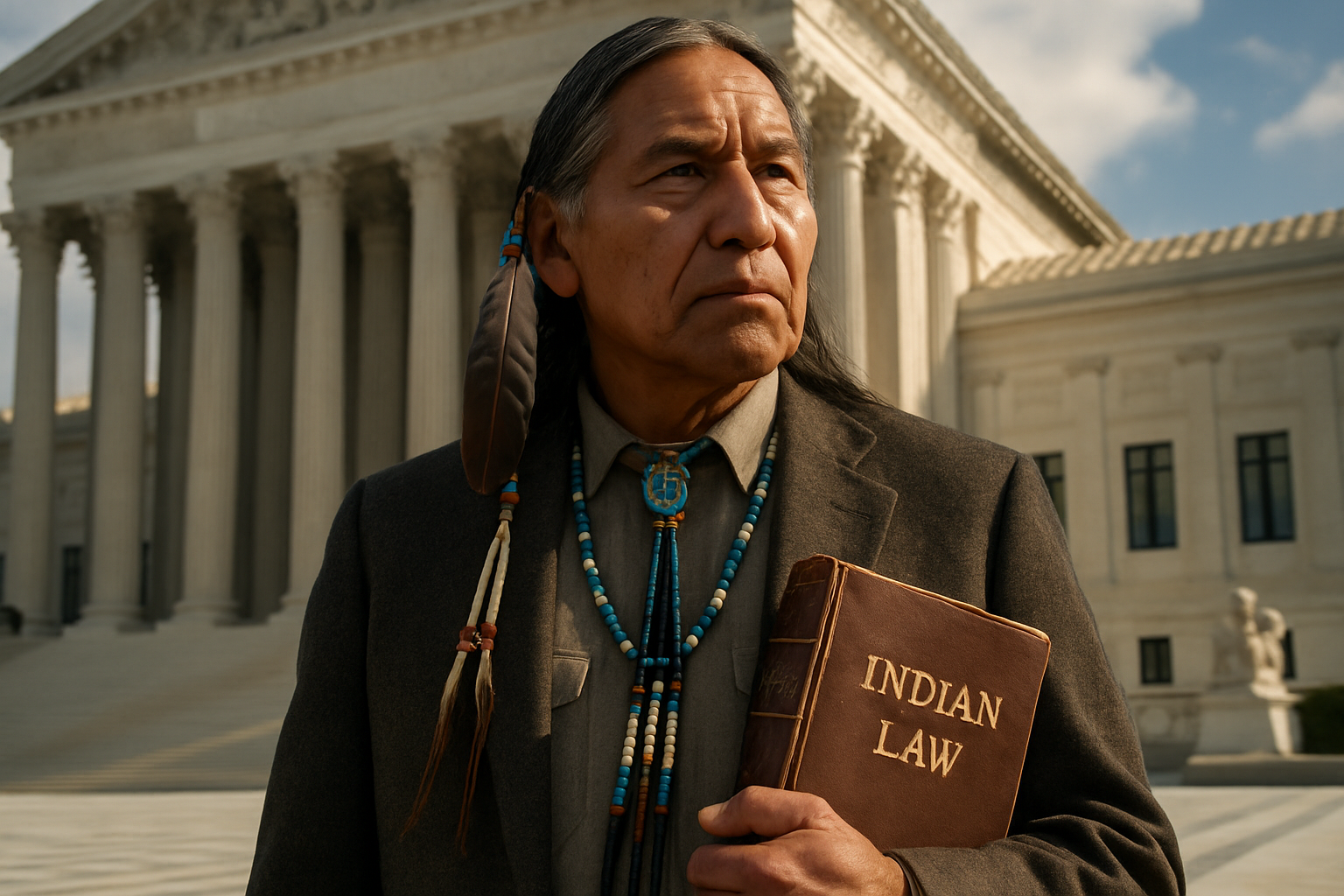

Tribal Sovereignty and Federal Environmental Regulation

Environmental protection on tribal lands represents a complex intersection of tribal sovereignty, federal authority, and ecological stewardship. Indigenous nations across America have historically maintained distinctive relationships with natural resources, viewing environmental management through cultural and spiritual frameworks that often differ significantly from Western perspectives. Recent legal developments have reshaped the environmental regulatory landscape on tribal lands, creating both opportunities and challenges for tribal governments. The tension between tribal self-determination and federal environmental standards continues to evolve through court decisions, legislative actions, and executive policies. Understanding this dynamic legal relationship provides crucial insights into broader questions of federalism, sovereignty, and environmental justice in contemporary American governance.

The Legal Foundation of Tribal Environmental Authority

Tribal environmental authority stems from the unique legal status of Native American tribes as “domestic dependent nations” with inherent sovereign powers. This concept, established through the Marshall Trilogy of Supreme Court cases in the early 19th century, recognizes tribes as distinct political entities with self-governing authority. Environmental regulation on tribal lands operates within this framework, where tribes maintain certain regulatory powers while being subject to congressional plenary power. The 1934 Indian Reorganization Act further strengthened tribal governmental structures, enabling many tribes to develop their own environmental departments and regulatory frameworks. Modern tribal environmental authority also draws from treaties that often contain provisions regarding natural resource management and protection. These historical legal foundations have allowed many tribes to implement environmental programs that reflect their cultural values and address reservation-specific concerns while navigating complex jurisdictional relationships with state and federal governments.

The Evolution of Federal Environmental Programs in Indian Country

Federal environmental regulation on tribal lands has undergone significant transformation since the environmental movement of the 1970s. Early environmental statutes like the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act initially contained no provisions specifically addressing tribal implementation. This created a regulatory void in Indian country as states lacked jurisdiction over tribal lands. The environmental “treatment as a state” (TAS) amendments of the 1980s marked a turning point, allowing qualified tribes to administer federal environmental programs directly. The EPA’s 1984 Indian Policy further clarified the agency’s commitment to tribal self-determination in environmental matters. These developments enabled tribes to receive federal funding for environmental programs and assume primacy for regulatory implementation similar to states. Despite these advances, the TAS process remains administratively burdensome, requiring tribes to demonstrate jurisdiction, regulatory capacity, and government stability. Consequently, tribal participation in federal environmental programs remains uneven across Indian country, with only a fraction of federally recognized tribes maintaining TAS status under major environmental statutes.

Jurisdictional Complexities and Legal Challenges

Environmental jurisdiction in Indian country presents intricate legal challenges that continue to shape tribal regulatory authority. The Supreme Court’s 1981 Montana v. United States decision established limitations on tribal civil regulatory authority over non-Indians on non-Indian fee land within reservations. This created complex jurisdictional questions for environmental regulation, particularly on reservations with “checkerboard” ownership patterns. The Court later clarified in Montana’s second exception that tribes may regulate non-Indian activities that “threaten or have some direct effect on the political integrity, economic security, or health and welfare of the tribe.” Environmental pollution cases often fall within this exception, though courts have applied varying interpretations. Recent litigation has tested the boundaries of tribal environmental authority, including disputes over water quality standards affecting upstream non-Indian users and air quality regulations impacting off-reservation facilities. These cases highlight the ongoing tension between tribal sovereignty and the interests of non-Indian stakeholders in reservation environmental management, creating continued legal uncertainty in this evolving field.

Climate Change and Emerging Tribal Environmental Leadership

Tribes have emerged as significant leaders in climate change response, navigating unique vulnerabilities while demonstrating innovative adaptation and mitigation strategies. Climate impacts disproportionately affect tribal communities due to geographical location, cultural connections to threatened resources, and historical socioeconomic disadvantages. The legal framework for tribal climate action draws from both inherent sovereignty and federal trust responsibility. Many tribes have developed climate adaptation plans that integrate traditional ecological knowledge with Western scientific approaches, creating models that have gained national recognition. Federal programs supporting tribal climate resilience have expanded under recent administrations, providing funding mechanisms for adaptation planning and implementation. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act notably included unprecedented funding for tribal climate initiatives. Additionally, several tribes have exercised their regulatory authority to address carbon emissions through renewable energy development and carbon sequestration projects on tribal lands. This emerging area of tribal environmental leadership demonstrates how tribal governments are asserting sovereignty to address contemporary environmental challenges while revitalizing traditional stewardship practices.

Cooperative Management and Environmental Justice Considerations

The evolution toward cooperative environmental management models represents a promising framework for harmonizing tribal sovereignty with broader environmental protection goals. Formal co-management agreements between tribes, states, and federal agencies have successfully addressed transboundary environmental issues while respecting tribal authority. These arrangements recognize tribal expertise and incorporate indigenous perspectives into resource management strategies across jurisdictional boundaries. Environmental justice considerations have gained prominence in tribal environmental law, addressing the disproportionate pollution burdens many reservations have historically faced. Executive Order 12898 and more recent federal policies require federal agencies to consider environmental justice impacts on tribal communities. Some tribes have developed their own environmental justice codes that integrate cultural values into regulatory frameworks. Despite these advances, significant barriers remain, including funding disparities, technical capacity limitations, and continued jurisdictional disputes. The future of tribal environmental governance likely lies in further development of cooperative frameworks that respect tribal sovereignty while acknowledging the interconnected nature of environmental systems across political boundaries.