Solitude Economy: How Intentional Isolation Creates Social Value

In a world increasingly characterized by constant connectivity and social overload, a counter-movement is gaining traction. The Solitude Economy represents a fascinating sociocultural shift where people actively seek and monetize alone time, transforming personal boundaries into marketable experiences. This phenomenon goes beyond simple self-care practices to become a complex social ecosystem where isolation is both a commodity and a currency in our hyperstimulated society. Read below to discover how intentional disconnection is reshaping our understanding of social capital and wellbeing.

The Paradox of Profitable Isolation

The Solitude Economy emerges from a fundamental tension in modern society: as our digital connections multiply, so does our psychological need for meaningful disconnection. This cultural shift has created a marketplace where experiences of aloneness—from digital detox retreats to single-person dining booths—command premium prices. Research by the Journal of Consumer Psychology shows that 67% of millennials and Gen Z are willing to pay more for experiences that guarantee periods of uninterrupted solitude. What makes this trend particularly fascinating is its paradoxical nature: people are socializing about their anti-social experiences, sharing carefully curated moments of isolation on social platforms, and collectively participating in organized solo activities.

This commercialization of alone time represents a significant departure from historical views of solitude. Where once isolation was often associated with punishment or social rejection, it now signals privilege and self-determination. The ability to disconnect has become a status symbol—a luxury that requires both financial resources and the professional flexibility to step away from constant availability. The resulting marketplace encompasses everything from noise-canceling technology and subscription meditation apps to high-end solo travel packages that promise “meaningful disconnection” at substantial cost.

The Neuroscience of Deliberate Disconnection

Scientific research increasingly supports the neurocognitive benefits of intentional solitude, providing biological legitimacy to this growing economic sector. Studies from the Max Planck Institute for Cognitive and Brain Sciences demonstrate that regular periods of solitude decrease activity in the amygdala, the brain’s fear center, while increasing neural connections in regions responsible for self-awareness and creative problem-solving. Neuroscientist Dr. Elena Martinovsky explains that “the brain in solitude activates its default mode network—a system critical for autobiographical memory, future planning, and moral reasoning that remains suppressed during social engagement.”

This neurological evidence has transformed solitude from a purely philosophical concept to a measurable health intervention. Corporations have responded by developing products that promise “scientifically optimized isolation.” Sleep pods, sensory deprivation tanks, and algorithmically timed disconnection apps all claim to deliver the precise type and duration of solitude needed for peak cognitive function. The medicalization of alone time represents a fascinating intersection of wellness culture, neuroscience, and capitalism, where isolation is prescribed and packaged like any other health product.

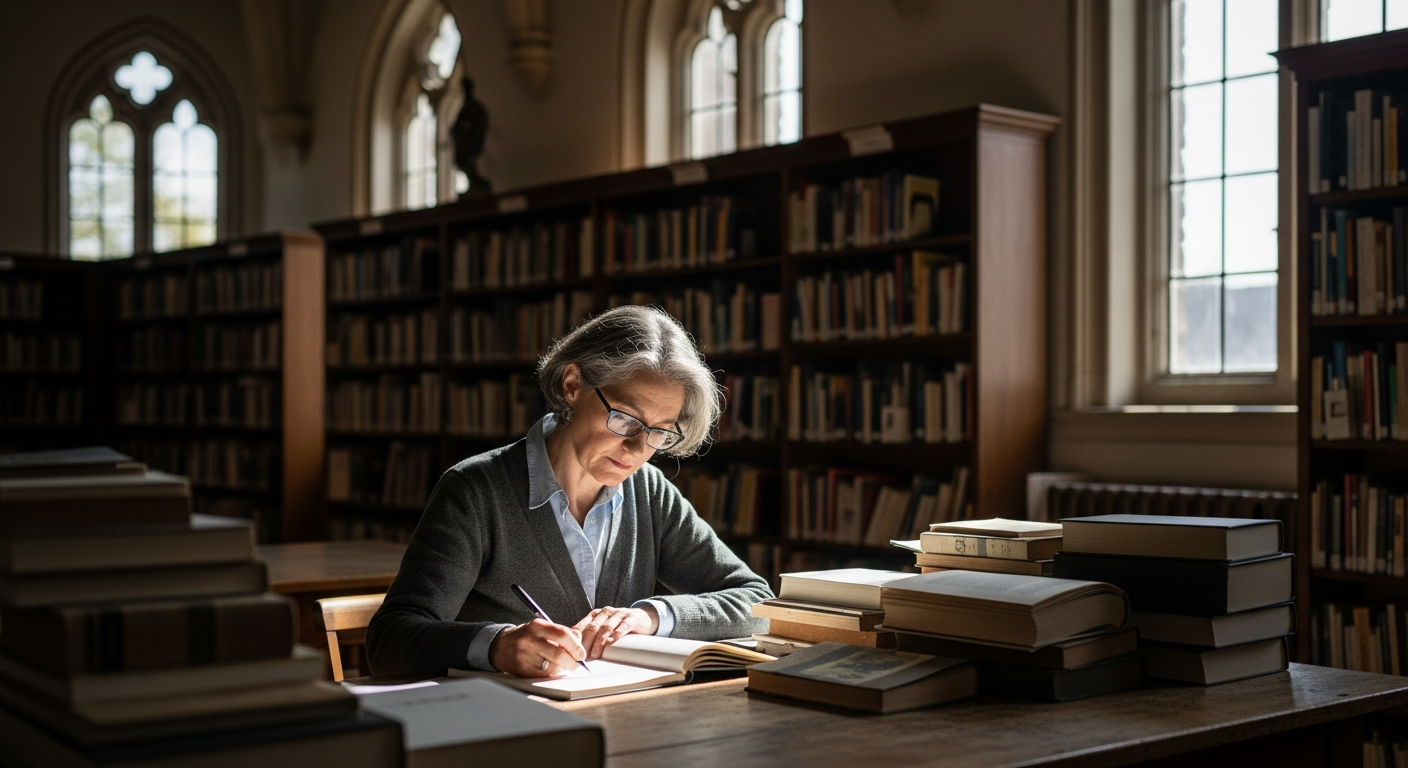

Identity Formation Through Absence

One of the most intriguing sociological dimensions of the Solitude Economy is how it redefines identity formation through negative space—who we are when no one is watching. Cultural anthropologist Dr. James Farrow describes this as “identity through absence” where “personal meaning is increasingly derived not from social performance but from chosen non-participation.” This represents a significant shift from social identity theory that has traditionally emphasized belonging and affiliation as primary identity mechanisms.

Survey data from the Pew Research Center indicates that 58% of Americans under 35 now consider “time completely alone” essential to their sense of self—a 22% increase from similar studies conducted in 2010. This introspective turn has particular significance for younger generations who have never known a pre-digital existence. For them, crafting boundaries around solitude becomes an act of self-authorship in a world where external validation is constantly available. The deliberate choice to withdraw, even temporarily, from social spheres serves as both personal statement and political positioning.

Architectural and Spatial Manifestations

The physical world is being reshaped to accommodate this new valuation of solitude. Urban planners, architects, and commercial developers are increasingly incorporating what sociologist Ray Oldenburg might call “third places for one”—spaces that are neither home nor work, but designed specifically for solitary engagement. Libraries are being reimagined with more individual meditation alcoves. Restaurants now offer solo dining booths with privacy screens. Parks feature single-occupancy relaxation pods. Even public transportation systems in cities like Stockholm and Tokyo have introduced silence-designated cars.

These spatial adaptations reflect a profound shift in how we conceptualize public space. Where urban design once prioritized social interaction and community building, contemporary approaches increasingly focus on creating microenvironments for temporary withdrawal. Real estate developers report that “solitude amenities” now rank among the top five most requested features in new residential buildings. This architectural trend represents not just a design preference but a fundamental recalibration of the relationship between physical space and social experience.

Digital Monasticism and Techno-Solitude

Perhaps the most counterintuitive aspect of the Solitude Economy is how technology both creates the problem and sells the solution. A new category of digital products specifically designed to facilitate disconnection—what media theorist Dr. Shoshana Zuboff terms “digital monasticism tools”—now generates over $4.2 billion annually. These range from apps that gamify periods of non-use to physical devices that block connectivity while preserving the comforting presence of technology.

This technological approach to solitude represents a fascinating compromise between digital nativity and the desire for mental space. Rather than advocating complete technological abstinence, the Solitude Economy embraces a more nuanced relationship with connectivity. Research from Stanford’s Human-Computer Interaction Lab suggests that this “techno-solitude” reflects a maturing relationship with digital tools—one that recognizes both their value and their cognitive costs. The willingness to pay for technologies that limit technology use speaks to a growing sophistication in how we negotiate our digitally mediated existence.

Ethical Implications and Social Inequities

While the commercialization of solitude offers genuine benefits, it also raises serious ethical questions about who can afford to disconnect. The ability to purchase privacy, silence, and uninterrupted time creates what sociologists call “solitude stratification”—a system where meaningful alone time becomes yet another resource unequally distributed along socioeconomic lines. Essential workers, caregivers, and those in precarious financial circumstances often cannot access the luxury of protected solitude.

This inequity extends beyond economic considerations to spatial and cultural ones as well. Urban density, household size, cultural expectations around family interdependence, and community obligations all influence how accessible intentional solitude might be. A 2022 study from the Urban Institute found that residents of low-income neighborhoods had approximately 70% less access to spaces suitable for solitary reflection than those in affluent areas. As solitude becomes increasingly commodified, the risk grows that this basic psychological need will become another axis of social stratification rather than a universal human right.