Behind the Screens: The Hidden World of E-Waste Recycling

The glossy screens and sleek metals of our electronic devices conceal a complex afterlife most consumers never see. When smartphones, laptops, and tablets reach their end-of-life stage, they begin a journey that spans continents and exposes harsh realities of the digital economy. E-waste recycling remains one of the most overlooked aspects of our tech-driven world. Despite growing awareness of environmental issues, many still don't know what happens to their devices after disposal. The process involves intricate supply chains, specialized techniques, and significant human cost. Understanding this hidden world reveals much about our relationship with technology and its true environmental footprint.

How Our Gadgets Become Garbage

The life cycle of electronic devices has shortened dramatically over the past decade. The average smartphone is replaced every 2-3 years—often not because it’s broken but because newer models offer marginally better features. This accelerating turnover creates mountains of potentially functional but discarded electronics. In 2023 alone, global e-waste reached an estimated 57.4 million metric tons, enough to fill over 1.5 million shipping containers. Only about 17% was formally documented as properly collected and recycled, with the remainder either landfilled, incinerated, or shipped to developing regions with minimal environmental oversight.

Behind this wasteful cycle lies a troubling economic reality: many devices are deliberately designed with repair difficulty and planned obsolescence in mind. Components are glued rather than screwed, special tools are required for basic maintenance, and software updates often slow older models. These practices push consumers toward replacement rather than repair, feeding the growing e-waste stream.

The Toxic Treasure Inside Your Old Phone

What makes e-waste particularly concerning is its composition. A typical smartphone contains over 60 different elements—nearly half the periodic table in your pocket. Gold, silver, palladium, and copper give devices their functionality but become hazardous when improperly processed. A metric ton of smartphones contains approximately 300 times more gold than a ton of gold ore, making e-waste theoretically valuable—if processed correctly.

However, improper recycling methods release harmful substances. Lead from circuit boards contaminates groundwater. Mercury from display screens vaporizes when heated. Brominated flame retardants, when burned, create dioxins linked to cancer and developmental disorders. In informal recycling operations—often using acid baths and open burning—these toxins enter soil, water, and human bodies with devastating consequences.

Industry experts estimate the recoverable value of materials in global e-waste exceeds $62 billion annually—a figure that could rise as rare earth elements become scarcer and more expensive. This economic potential remains largely untapped due to insufficient collection systems and primitive recycling methods in many regions.

The Global Journey of Digital Detritus

Despite regulations like the Basel Convention, which restricts transboundary movements of hazardous waste, millions of tons of e-waste still travel from wealthy nations to developing countries. Investigations by environmental watchdogs have tracked containers of “second-hand electronics” from North America and Europe to destinations in Africa and Asia, where environmental regulations are less stringent.

In Ghana’s infamous Agbogbloshie district, often called the “world’s largest e-waste dump,” workers as young as six break apart devices with hammers and stones. In parts of China’s Guiyu region, despite government crackdowns, informal operations continue extracting metals using methods that poison local water supplies. Workers often earn less than $10 daily while exposing themselves to toxic chemicals without protective equipment.

The economics driving this trade are straightforward: shipping waste overseas costs a fraction of processing it domestically under strict environmental standards. A container of “broken electronics” sent to Ghana might cost $2,500 in shipping but would require over $20,000 to process properly in the United States or European Union.

Tech Companies Face Their Waste Problem

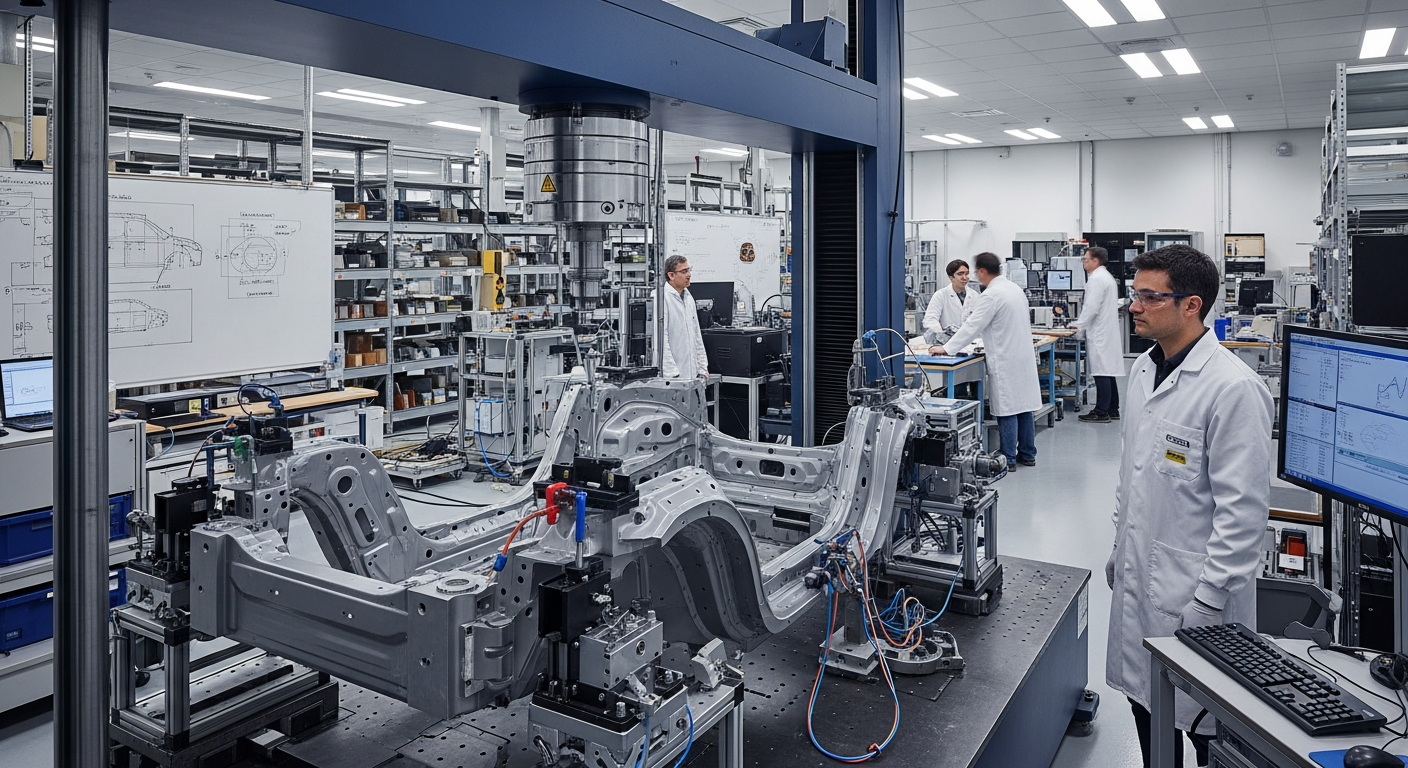

Under mounting pressure from environmental groups and conscious consumers, major technology companies have begun addressing their e-waste footprint. Apple has invested in sophisticated recycling robots like “Daisy,” which can disassemble 200 iPhones per hour, recovering valuable materials with minimal environmental impact. The company claims to have recovered 61 million pounds of materials through its recycling programs in 2020 alone.

Samsung launched its Galaxy Upcycling program, allowing older smartphones to be repurposed as IoT devices rather than discarded. Microsoft has pledged to achieve “zero waste” operations by 2030, including taking responsibility for end-of-life products.

These corporate initiatives represent progress but face criticism for focusing more on public relations than substantial change. Many environmental advocates point out that truly sustainable electronics would prioritize repairability and longevity from the design phase—attributes often at odds with the industry’s profit model of regular replacements.

The Future: Circular Electronics

The concept of circular electronics offers a potential path forward. Unlike the current linear model (take-make-dispose), circular systems design out waste and pollution from the start. This approach incorporates modular design, standardized components, and business models based on service rather than ownership.

Companies like Fairphone demonstrate this philosophy with devices designed for easy repair and upgrade. Their smartphones feature removable batteries, replaceable screens, and accessible components—extending useful life to five years or more, compared to the industry average of 2-3 years.

Policy frameworks are gradually shifting to support this transition. The European Union’s Right to Repair legislation, expanded in 2022, requires manufacturers to make spare parts available for up to ten years and provide repair information previously kept proprietary. Similar initiatives are gaining traction in parts of the United States and Asia.

What Consumers Can Do

Individual actions matter significantly in addressing the e-waste challenge. Extending device lifespans through careful use and repair represents the single most effective way to reduce electronic waste. When replacement becomes necessary, researching companies’ recycling programs and using certified e-waste recyclers ensures materials are processed responsibly.

Consumer awareness also drives corporate change. Companies respond to market pressures, and growing demand for repairable, sustainable electronics has already influenced product development at major manufacturers. Supporting right-to-repair legislation and companies with demonstrated environmental commitments helps accelerate the transition to more sustainable electronics.

The hidden world of e-waste reveals the full cost of our digital lifestyle—a cost often borne by vulnerable communities and ecosystems far from where these devices are used and enjoyed. As awareness grows and technologies improve, the opportunity exists to transform this toxic legacy into a model of sustainability, where today’s gadgets become tomorrow’s resources rather than persistent pollution.